The DO Points

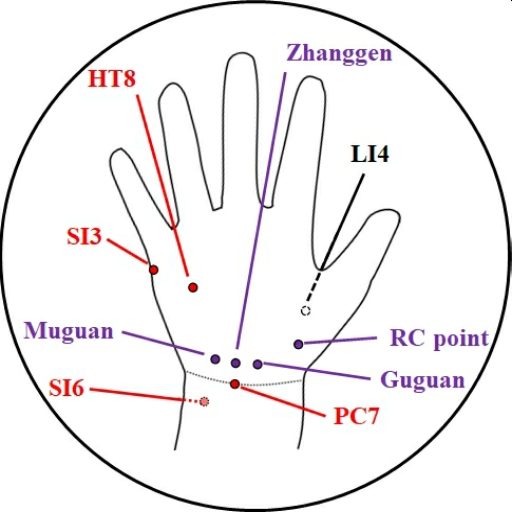

One thing that emerged from our reviews was a clustering of points on the hand used (separately) to treat pain in the heel, usually on the contralateral side. I have grouped these together, as the Diagonally Opposite points (DO points for short). They are illustrated above.

A significant subgroup of our sources used these points, all from China, yet quite disparate in their rationales. Some simply say “use upper for lower”; e.g. Chen 1 used SI6; Liu 2 used PC7; Ouyang 3 used “corresponding points on the palm” without giving details.

Some go with the notion of specific efficacy. Heel pain is given 4 as a specific indication for using the points Muguan and Guguan (a pair of points located approximately where I have indicated on the diagram, and located by finding tenderness). Zhang et al 5 hypothesise that “PC7 had a better effect than LI4 in relieving pain due to plantar fasciitis” and claim to have demonstrated that “acupoint PC7 has a specific effect for treatment of plantar fasciitis …”

Others apply the ‘principle of opposites’ in terms of meridian theory, in a variety of ways:

- Reaves6 suggests HT8 as “shaoyin corresponding point” although he doesn’t say what it is corresponding with. I wonder why this point, rather than HT7?

- Nie et al7 also invoked Shaoyin, but then used different logic (along the lines of: Bone pain – Kidney – Leg Shaoyin – Arm shaoyin – branches to Pericardium) and recommended a “newly discovered” point, Zhangen.

- The connection between KI, BL and SI via Taiyang is invoked in papers by Gao 8 and by Feng 9, leading to the use of SI3, which they choose (as the command point for GV) to raise yang in cases of deficiency.

- The Yangqiao meridian was given 10 as a rationale for choosing GB20 (because Yangjiao “originates in the heel” and GB20 is the “corresponding point” to the heel). As the command points for Yangqiao are BL62 and SI3, I might have expected this combination to have been used, but this has not appeared in the research to date.

- I would like to add Taiyin into the mix, from my own experience. When I had PF, I had a trigger point on the SP meridian (Leg Taiyin) in Abductor hallucis, and the point of most tenderness on the hand was on the LU meridian (Arm Taiyin) near LU10 (RC point on the diagram).

This ‘principle of opposites’ was perhaps first articulated in the Ling Shu as “use upper for lower” (or vice versa) but its intuitive use is widespread today among acupuncturists of all schools, in my experience. How can we build on this? How should we choose between these points, in any given case?

Hopefully, if a pattern differentiation has been done for the individual patient, a clear choice might be apparent. But that is not what was done in the research reviewed. Instead a categorical approach was taken, where the approach is generalised to a cohort of patients shoe-horned into a diagnosis.

I wonder – are there safe generalisations we could make? We could debate finer points of Shaoyin v Taiyin v Yangqiao but maybe we don’t need to. Zhang et al 5 introduce the idea of anatomical mirroring of the heel in the hand. This brings to mind Sherrington’s classic ‘The Integrative Action of the Nervous System’.

We know that locomotory reflexes are organised so that the movements of opposite limbs are coordinated (as the right leg flexes, the left leg and right arm extend, and so on), so I wonder if a similar pattern underlies our sensory pathways too. Could it be that a pain in the heel is somehow related to a change in the sensory function of the ‘heel of the hand’? And that sensory input on the hand could influence (in some specific way) pain pathways from the heel? I have not seen anything published on this; have you?

Following this hypothesis, one might expect to find physiological changes to help identify the most useful points, such as electrical conductivity, or localised hypersensitivity. Tenderness of points is often given as a rationale for choosing them.

So what is the bottom line? For practice: there are some tactics that fit naturally into certain strategies:

- If you must stick to EBM, the DO point to consider is PC7.

- If using the local Ashi, search for tender points also at the ‘heel of the hand’ in the vicinity of Zhanggen, Muguan or Guguan.

- If you found tender points along the SP meridian, or a trigger point in Abductor hallucis, consider Taiyin and look for a tender point near LU10.

- If you are sure the KI meridian is involved and are using KI3, you might consider HT8 as a distant point along the Shaoyin meridian.

- If working with Yangqiao, using BL62, then adding the other command point SI3 may enhance the effect, particularly if there is a need to raise KI yang.

- SI3 also makes sense as a distant point along Taiyang, in combination with BL62 or, indeed any other BL points on the leg.

Finally, here are some suggestions for research projects:

- Mapping tenderness of DO points in patients and controls would be an interesting study.

- Similarly, mapping other parameters could be useful, such as: electro-conductivity, thermography or the ‘active points test’ 11.

- It may be tempting to design an RCT to compare the effectiveness of these points against one another but I would be wary of the assumption that any single point is ‘the’ point for heel pain. Please remember that patients vary and these DO points traditionally have different functions; then be very clear about what hypothesis you are testing.

- If the aim is to build on Zhang et al’s work on PC7, any of the other DO points might make a better comparator than LI4. Perhaps one could compare PC7 with whichever point was indicated by tenderness in each patient. And, of course, it would be ideal to include a proper no-treatment control group (waiting list, or dummy needling) to give us a measure of natural remission, etc.

References:

- Chen C. Using Yanglao (SI6) as the main acupoint to treat heel pain by acupuncture. Zhong Guo Zhen Jiu 2002; 22: 400.

- Liu ZA. Hand needling treatment for painful heels: a clinical observation of 20 cases. International Journal of Clinical Acupuncture 1999; 10: 95-97.

- Ouyang Q and Yu G. Acupuncture at upper limb points for pain of the sole: a report of 73 cases. International Journal of Clinical Acupuncture 1996; 7: 499-501.

- Borten P. Tung Points and Unique Applications of Points on the 14 Main Channels as Presented by Wei Chieh Young, Richard Tan & Steven Rush, http://peterborten.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Tung-Point-Compilation1.pdf (accessed 26/2/14).

- Zhang SP, Yip TP and Li QS. Acupuncture Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis: A Randomized Controlled Trial with Six Months Follow-up. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2009; 23: 23. DOI: 10.1093/ecam/nep186.

- Reaves W. Plantar Fasciitis: Acupuncture Treatment of Heel Pain., https://www.jadeinstitute.com/posts/plantar-fasciitis-acupuncture-treatment-of-heel-pain/ (2015, accessed 14/05/2021).

- Nie H. Puncturing Zhanggen in treating 106 cases of calcanodynia. International Journal of Clinical Acupuncture 1993; 4: 201-202.

- Gao H. Analysis of 30 cases of heel pain in middle age and elderly patients by acupuncture in HouXi (SI3) acupoint. J Henan Univ (Med Sci) 1998; 17: 54-55.

- Feng J. Acupuncture treatment of heel pain using Houxi [SI3] point. Ch Ac & Moxib 2002 22: 400

- Chen SC. Needling Fengchi in treatment of pain in the heel: a report of 17 cases. International Journal of Clinical Acupuncture 1996; 7: 209-210.

- Marcelli S. The Active Points Test. London: Singing Dragon, 2015.